ICC Finalizes Opinion on B/L Freight Details

At its first quarterly discussion session of 2026 on 27 January, the ICC Banking Commission finalized ICC Opinion TA958rev. It

The views expressed by the authors in this publication do not represent their employers, any entity, government, or agency. Any content should not be interpreted in any capacity as regulatory guidance, recommendations, or interpretations of law. Such expressed views are to be considered individual opinions and perspectives.

Editor's note: This paper is reprinted with the permission of the ITFA, and is available here.

The manipulation of price as a technique of trade-based money laundering (TBML), was strongly emphasized by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) in its 2006 TBML publication.[[1]] Since 2006, industry organizations such as the Bankers Association for Finance and Trade (BAFT), the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), the Institute of International Banking Law and Practice (IIBLP), Wolfsberg Group, and regulatory guidance from the Joint Money Laundering Steering Group (JMLSG) Prevention of Money Laundering/Combating Terrorist Financing[[2]] and the State Bank of Pakistan’s Circular Letter No.08 demonstrate that controls are still needed or expected.[[3]]

Due to the complexities of international trade, the successful incorporation of a price mis-invoicing control into a compliance program can take many forms. Such complexities include the quality and types of documents received, the vagueness and lack of contextual detail associated with open account trade products, and the suitability of technological approaches to detect and manage true and false positives.

To tackle the ongoing manual nature and complexity of trade, institutions can first explore the components of their risk profile, resources available, and overall skillsets therein. The advantages of employing new technologies based upon strong and reliable datasets could facilitate the implementation of more advanced methods such as Large Language Models (LLMs), machine learning, or other methods such as a mirror analysis of trade data. This method of analysis compares one country’s set of trade data against another to determine if there are large value discrepancies which could be interpreted as a possible area of focus.

Underlying all these methods are the requirements for skilled resources to understand the product offerings, the types of goods being shipped, and economic flows. To assist, these organizations could conduct skillset reviews, develop targeted training, and tailor academic testing. These areas should be specifically designed to the organizations risk profile and not necessarily an off the shelf training product.

The paper’s analysis assesses the implications for institutions across the trade lifecycle and the various lines of defense when managing compliance. The discussion includes the potential for automated price screening checks, integration of price screening in compliance programs, and the potential future of price verification controls. The advocates and opponents of screening the actual price of a goods shipment all underscore the need to balance effective compliance versus the facilitation of international trade and overall client experience.

The ability to conduct TBML in and of itself is not simple and requires the weaving of several money laundering techniques together. Combined with the rapid growth of global trade, supply chain misuse has been subjected to the actions of individuals and groups seeking to perform illicit functions. Within trade, obvious mis-invoicing is still widely used and disguised under complex levels of obfuscation, documentation, or confusing terms. Reinforcing this point are several estimates and reports highlighting the substantial extent of price mis-invoicing in global trade. In its March 2020 publication, Global Financial Integrity estimated that between 2008 and 2017, trade and commercial financing were used to launder approximately $9 trillion in illicit funds. For 2018, the United States Government Accountability Office referenced price mis-invoicing at $278 billion moved out of, and $435 billion moved into the United States.[[4]] More recently, in a study conducted in June 2024, the United Arab Emirates’ Financial Intelligence Unit analyzed suspicious transaction reports for a two-year period and identified 11% of the TBML reports “whose stated prices are substantially more or less than those in a similar market situation or environment.”[[5]]

Equally, and not just from a money laundering perspective, there are historical examples of fraud relating to the mis-invoicing of services and goods reinforcing the statistical analysis by government agencies. In 2014, using a scheme of fake invoices, a Mexican oil services company was found to have initiated a fraud valued at approximately $400 million in loans and other bank instruments.[[6]] The company issued fake invoices stating several services performed on behalf of Mexico’s state run oil company. These services were non-existent and subsequently allowed the Mexican oil services company to raise advance payments from the financial sector. In Pakistan, customs authorities accused several solar panel manufacturers of processing $246 million worth of imports through an over-invoicing scheme. The imports were inflated to assist in the outbound payment of remittances while disguised as legitimate trade. The actual value of goods was estimated at $303 million, marking a shortfall of $57 million.[[7]] Finally, as a part of the 2020 FATF Egmont Group Report, countries such as Germany and the United States highlighted in their National Risk Assessments the continued use of over-and-under invoicing of goods in financial crime.[[8]] Therefore, the ongoing and periodic examples of fraud and TBML strongly imply that operators within the global supply chain cannot ignore the consistent reinforcement and importance of reviewing product pricing.

If there is a general consensus that price verification checks should occur, such controls should be placed within compliance programs to prevent unnecessary client disruption and ensure the optimal level of accuracy and efficiency. As under-and-over invoicing generally requires collusion between parties (fraud if only one actor), the chances of one specific typology highlighting over-and-under invoicing are remote. Usually there are multiple red flags which can be detected and mitigated at the initial document review stage.

Within the current context of sanctions and export controls, checks could be done further upstream in compliance processes. The argument for doing pre-transaction checks versus post checks, is to combat the potential existence of fraud, sanctions, and export control violations. The post-transactional workflow gives companies the flexibility to select a statistically viable sample based upon a risk frame, that can target areas of higher risk, and thus increase potential productivity, efficiency, and time to execute.

Obvious mis-invoicing could still be used and disguised by the inclusion or omission of complex levels of trade documentation, or confusing terms. Seasoned staff resources, trained in the expertise of trade finance, can easily focus and find red flags in the existing document check and subsequent review processes. When these skills are appropriately brought to bear, an organization can more readily weigh its inherent risk exposure to TBML and specific typologies, such as over-and-under invoicing, and when they potentially occur. This can be achieved through an analysis of skills, resources, available tools, and budget.

When developing training, an organization, regardless of its role in the trade lifecycle, should understand the product offerings, the types of goods being shipped, and economic flows. To assist, these organizations could conduct a skillset assessment across different control levels, review use cases, and conduct tailored academic testing. These areas should be specifically tailored to the organizations risk profile and not necessarily an off the shelf training product. Training should be adapted based upon the types of documentation that can be expected within a transaction. Different entities within the supply chain will receive varying levels of complexities of documentation and therefore should not be expected to train or operate outside what would be considered a reasonable level of due diligence.

While on paper this can sound expensive, organizations can utilize motivated and dedicated staff to create manual or even digital low-cost, quick to setup, and engaging training. In this example, regular training and customized testing to evaluate staff knowledge are developed at the end-user level and actual point of execution. This reduces the possible negative perception of just another generic digital training video, but encourages staff to repeatedly engage in multiple scenarios, granting them more precise and efficient evaluation of trade documents. Such engagement could create the mentality of “rage to master,” which Ellen Winner describes as a psychological drive to master a subject. This could also have the second order of effect, spurring others to become interested and involved.[[9]] Trade knowledge can, therefore, become inculcated into an effective control structure and not just the addition of another red flag to an internal review checklist.

Price checking today is primarily carried out by institutions on a manual basis. Staff processing transactions use their knowledge and experience to determine if a quoted price appears to be under-or-over invoiced. In certain circumstances where goods are specialized, for example chemicals or high-tech machinery, the institution may apply external pricing sources to assist in the evaluation process. Equally, the institution may refer to its own historical data of a similar nature to offer a price comparison check for the traded goods.

As a starting point, price is not currently evaluated as an outright screening check, but more as an investigative control, subsequent to additional red flag reviews. It is not conducted on all transactions, and it generally forms a segment within an overall risk and compliance screening program incorporated alongside other red flag identification tasks. Therefore, institutions tend to concentrate on other typologies which highlight overall trade risk associated with price, goods, and similar transactional inputs. These typologies can include the identification of unusual shipping routes, certain high-risk goods, invalid weights, measurement of the goods in transit, or the overall economic sense of the trade transaction.

In certain cases, an initial evaluation of the trade or transaction containing unmitigated higher risk attributes may prompt the next step to enhanced due diligence. If the route of the goods, including the load and discharge countries, or goods and customers involved were deemed to be higher risk then a detailed investigation into price could be required. Furthermore, when developing more targeted red flags and typologies, such as moving beyond a traditional geographic risk score, entities could consider independent studies and analysis on differences in origination and destination goods values. For example, analysis conducted on US exports can determine which goods and export locations have historically been found to capture the likelihood of price or goods mis-invoicing. Here, the price differential offers a tactic of a more layered approach, factored into a risk appetite or other risk assessment scoring methodology, instead of acting on an isolated transaction by transaction analysis.

To assist in the understanding of which countries, goods and products are most at risk for mis-invoicing, it is possible to compare import and export prices at the country level. Using 4-digit Harmonized Schedule (HS) Code data, a mirror analysis of a country's reported export trade values with a partner’s corresponding imports over the same time, can potentially highlight price mis-invoicing attributes. The analysis could be more focused if an organization has access to 6-digit HS code data, either from international organizations or specific local government databases.[[10]]

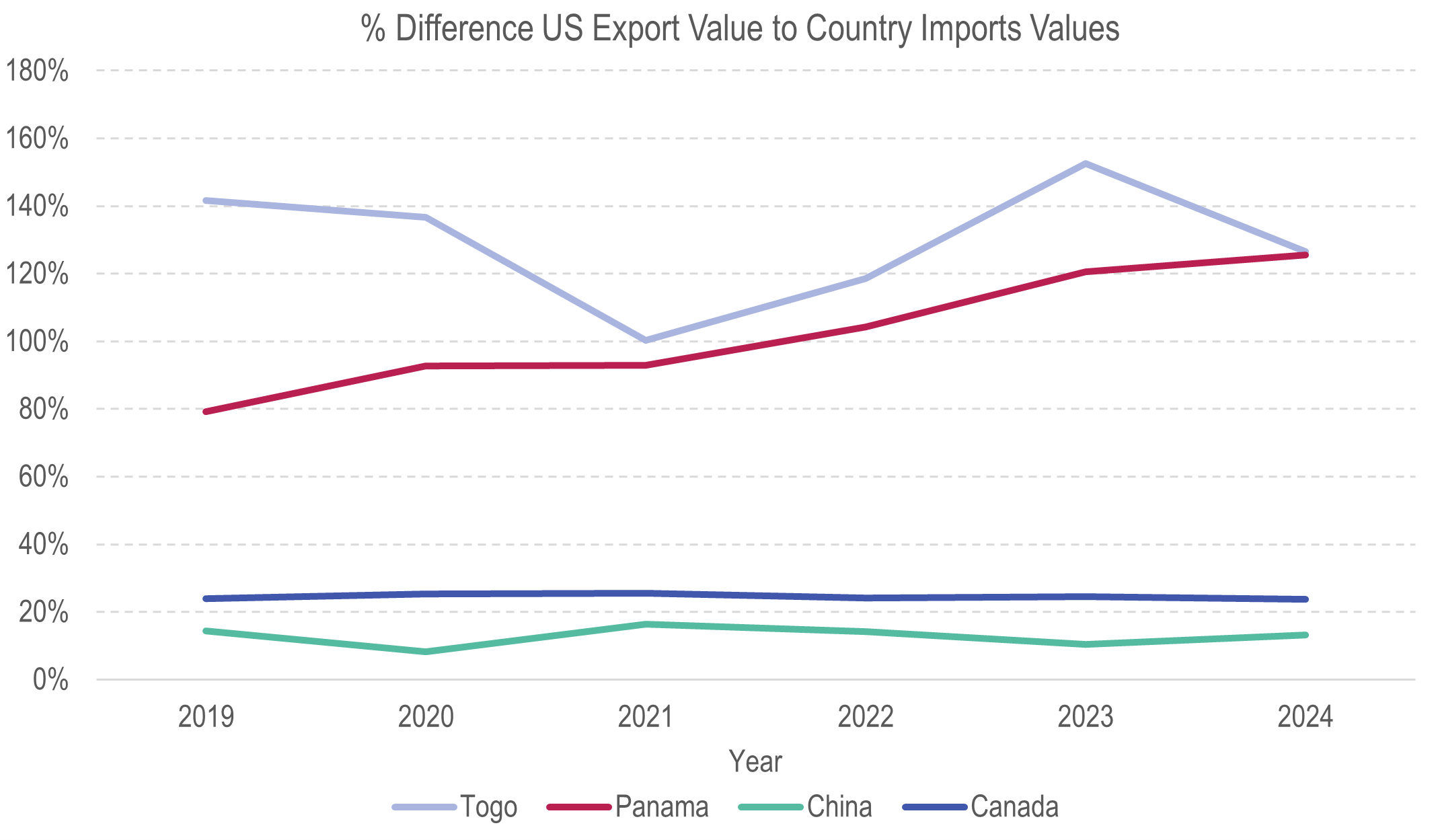

The analysis described here captures annual US export trade data between 2019-2024 for goods and products across the 4-digit HS Code schema.[[11]] As a comparison, corresponding data from the import countries is captured for the same goods and products. Using a mirror methodology on customs price data, it is possible to determine which US trading partners display a higher degree of price differences and which products and goods historically displayed the potential for over-and-under pricing. The analysis could assist institutions in narrowing their focus based upon trade supply chain corridors, instead of concentrating efforts primarily at a transaction or invoice-by-invoice level. Customs data could be helpful for risk assessment purposes or to narrow the number of transactions for when pricing risk could be evaluated. For example, between 2019 and 2024, Togo and Panama showed considerably higher import value for goods exported from the US. When compared to Canada and China import prices, the difference with US exports was lower, highlighting price discrepancies could be potentially attributed to other reasonable trade factors such as freight, insurance, or other associated costs.

The value of goods reported by US import and Macau export data highlight a differential range of 66% to 129%. Comparisons between Singapore exports to the US ranged from 11% to 22%.

Taken holistically and comparing each country's import and export data for the same basket of goods, utilizing bilateral export and import pricing could influence a decision on when to perform additional due diligence. Again, data of this nature should not be considered in isolation but with the presence of other indicators of TBML or fraud risk.

As part of a risk assessment process, analyzing country export and import data is a potential approach. Another is conducting an analysis of higher risk goods. The analysis assumes the availability and receipt of higher quality standardized data, the attainability of classifying goods codes (HS Code), and reasonable goods descriptions. However, strong consideration must be afforded to institutions that might have a lower inherent risk profile or access to the data for such an analysis.

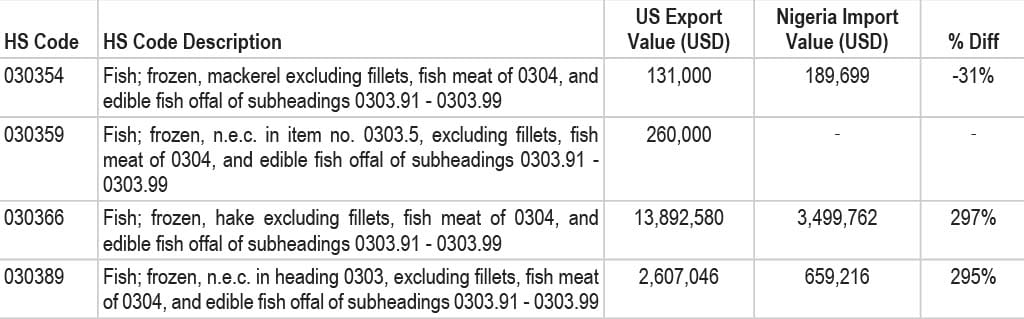

As an example, shown in Table 1, a comparison of import and export prices for frozen fish shipped between Nigeria and the US, identifies disparities in monetary value. Certain frozen fish, at the 6-digit HS Code level, exhibit approximately 300% difference between export and import values reported by the customs authorities of both countries. It is difficult to determine whether the difference in price is due to price mis-invoicing as the delta in prices could be attributed to freight and insurance costs, discounting, misreporting of certain shipments or a misalignment of monthly prices by customs. Raw data acquired from government and customs agencies may not always be enough to ascertain the root cause or possible reason for the price differential, negating the advantages of a transaction-by-transaction analysis. Furthermore, US shipments of frozen fish to Nigeria also highlight certain issues with goods classification. The HS Code 030359 accounts for the US export of $260,000 of frozen fish in 2024, while the Nigerian import classification for the same code contains no import record. At face value, it appears the goods within this HS Code were not classified correctly, either on the export or import side. While this may be one potential reason, there are others that could be considered. The implications are that if official country trade data can only highlight a potential issue, rather than pinpoint or narrow down its cause, institutions will be required to further analyze and interrogate other datasets and materials to determine if price mis-invoicing occurred in a particular transaction.

This information can assist in the ability to deep-dive on certain practices and filter out unwanted noise. Other entities such as customs agencies might be better equipped to view the information and shipment level. To complete the lifecycle, institutions which collect customer and transaction data could employ advanced analytics to complement economic trade data.

Those institutions with price checking directly integrated into their risk, screening and supplier analysis programs have sometimes used thresholds to determine the potential of price mis-invoicing. These thresholds have been set to manage a price variance from certain established benchmarks. If the transaction, after analysis, contains a price which is deemed to break the threshold i.e. the fair market value price, then further investigation is warranted to understand the reason. The unit price could be compared to an industry or market average. However, many have argued this is difficult to achieve due to the multitude of different goods shipped around the world, level of documentation received, vague goods descriptions, and missing goods classifications. Furthermore, to determine a threshold breach, a large homogenous data set would be required for resources to review each invoice line item. A potentially overly burdensome, if not impossible, exercise for some institutions.

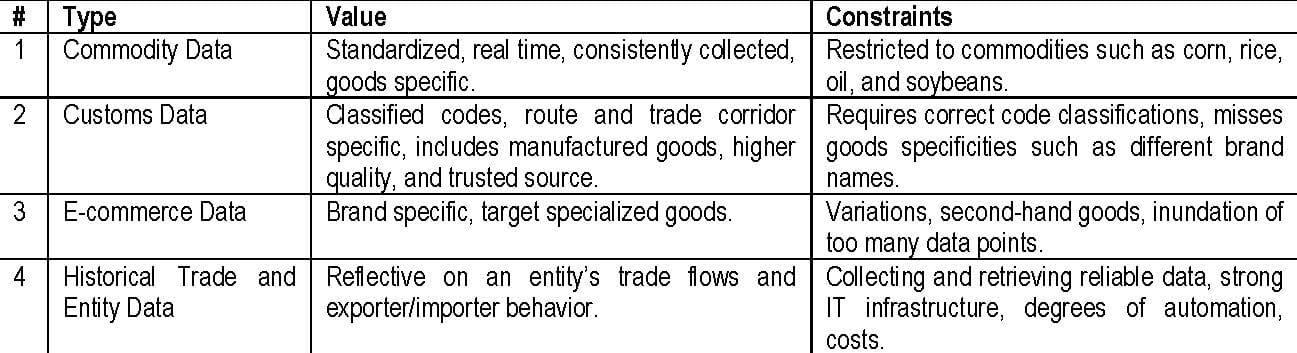

When looking at thresholds, to establish market prices, commodities lend themselves to be the simplest to analyze. Public and historical data can quickly be captured and analyzed for large variances. Commodities quoted on exchanges or formulated as benchmark prices provide accurate and up to date values. While these commodities are limited to energy, metals, and agricultural markets, they do offer prices on a granular basis which can also be specific to actual country or commodity grades. Rice, for example, is traded on the CBOT exchange and classified in accordance with rough or milled grades. Each category comes with its own specific price. Many commodities are also benchmarked for price purposes, the Japanese Korean Marker (JKM) Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) contract is a spot price for LNG in northeast Asia.[[12]] In many cases, commodity prices will provide a spot price ensuring any price check conducted by an institution will be relevant and historically understood.

Perhaps the commodity pricing approach is not necessarily reflective of the current environment, as typologies associated with price manipulation lend themselves to more complicated or generic goods. Here the underlying deals between exporters and importers are not indicative of specific fees or discounts associated with areas such as shipping costs, buying in bulk, and insurance. Trade finance institutions have traditionally found that thresholds can generate false positives as the previously associated costs can skew actual unit pricing results. Therefore, to determine a threshold setting with a one-size-fits-all or individual goods classification value seems unfeasible. To identify if potential manipulation is occurring, organizations could view the overall context of the transaction's economic viability, additional risk factors involved, and the historical behavior of buyers and suppliers. To accomplish this, well-seasoned and trained resources with comprehensive knowledge of supply chains are required. Some institutions have considered the use of more mathematical approaches for detection, but this requires the collection of quality data and behavioral analysis of an entity’s buyer or suppliers.

Commodities can be found from open-source references such as exchanges (EEX, CME, ICE etc.), benchmarks (JKM, TTF etc.) and price assessments (Platts, Argus etc.). Websites also offer platforms for overall commodity prices such as Business Insider and Yahoo with information across the main traded commodities. But herein lies one of the traps to open-source data. It will not cover the entirety of market price data needed for an institution’s trade flows which would require additional information on containerized, manufactured goods. Also, commodity prices may need to be evaluated at the specific date on which the trade was referenced, as current spot prices might be affected by severe seasonal or market spikes. This increases the time required to undertake an assessment and the need for experienced trade professionals.

Another potential data source is custom prices. Price data from customs and government statistical authorities are managed, collected, and distributed to a high standard. The content offers insights into price values by trade corridor and can organize data by maximum, minimum or average price across different timeframes. The accuracy of customs data implies that goods are weighted to the country of origin and discharge, accounting for price variations by quality or type. For example, garments shipped from Bangladesh to Japan will offer a price specific to that market. Of course, there are disadvantages with customs data. Primarily, the vastness of the content spans nearly 20,000 different categorizations organized within the Harmonized Schema (HS) at the international 6-digit level. Some have called the correct assigning of a HS Code an art form, where no two individuals see the same good the same way. For example, is Kimchi a fermented product (HS Code 200100) or a specific vegetable (HS Code 070490).

E-Commerce price data from consumer shopping websites such as eBay, Amazon, Alibaba, and others have a vast database of current price values for manufactured goods. The vastness of the e-commerce platform data contains potential pitfalls and does not necessarily lend itself well to the transaction screening process. E-commerce listed goods are merged into similar categories, such as new, used, or old new stock which can skew an actual price on a single item at the brand or model level. Equally, the range of prices for an individual item can be broad as discounting and shipping can affect the final cost of the listed goods. Other than categorized goods and the costs of facilitating trade, unbeknownst to buyers, prices could be manipulated to commit fraud. To determine a reasonable price, a document reviewer would need to collect several data points, between 10 and 30, and calculate metrics such as median and average prices for goods from the exporter and importer perspective. If an organization has access to quality data, can apply behavioral analysis methodologies, understands its customers business, and supply chains, this could be considered reasonable.

Evaluating customers, sectors and wider industries offers a more precise insight when evaluating goods price for mis-invoicing. Institutions will have customer and supplier databases with information on shipments, shipping routes, third parties and other important information. This also highlights the need to evaluate transactions holistically and in keeping with a customer’s or supplier’s profile. However, trying to conduct the previous analysis in a manual fashion would adversely impact the customer experience, potentially costly, especially if conducted at the time of purchase or red flag review of an inflight transaction. To cope, organizations can conduct post transaction reviews either through random sampling or through a pre-determined risk frame. On the other hand, there are some benefits to the use of e-commerce data when determining the price of an item. If available, the capture of goods at a granular level at the brand, serial, or model number can offer a more specific value when compared to other price sources. The use of price and open-source data could reveal unique specialty goods that can often be used to complicate or hide transaction value. For example, the specific price of a Canyon Aeroad CF SLX 8 Di2 bicycle is more likely to be found on e-commerce websites and likely to be reflective of its true value. Such an approach can be useful in detecting manipulation on specific widely-sourced goods used for TBML, such as electronics, as cited by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) in its recent advisory.[[13]]

Conversely, when reviewing the table above, entities across the supply chain are essentially using a myriad of open sources that are not standardized across jurisdictions and types of businesses. Reviewers could be focused on the first returned search result or influenced by personal experiences. This could mean someone who is a car enthusiast sees the value of something being manipulated while a different person might take it as stock value or conduct further research using different sites.

The advancement of technologies such as GenAI, machine learning techniques, and trade corridor data could assist organizations in the development of a catalogue of prompts, scripts, or other monitoring techniques. The ability to use correct prompts to return specific information on the current and historical cost of a set of goods, grades, and country variations promises further simplification with LLMs than previous search methods. This comes with strong caveats that staff resources would need the knowledge to enter the appropriate prompt.

To operationalize, organizations would need to determine the control location, and who would have the capabilities to execute. This could present additional challenges and perhaps not best placed as a decisioning or mitigation within its own right. Instead, the use of LLMs could be a part of an investigative control process. Importers, exporters, freight forwarders, customs, and financial organizations could consider using open-source data models for goods classifications and generic invoice pricing but need to be careful not to fall into a trap of following an inappropriate thread.

Like other open-source methods used, it should be a starting point and would require justifications as to why certain digital decisions or selections were made. It also begs the question of how far does the reviewer go to reasonably create a conclusion. This could result in inappropriate escalations, transactions being stopped, and other disruptions to a client's business. Further complications to consider would be the handling of proprietary information, data privacy, and use of public databases.[[14]] To operationalize these actions and show why specific decisions were made, a series of training, prompts, and documentation standards would need to be codified and updated.[[15]]

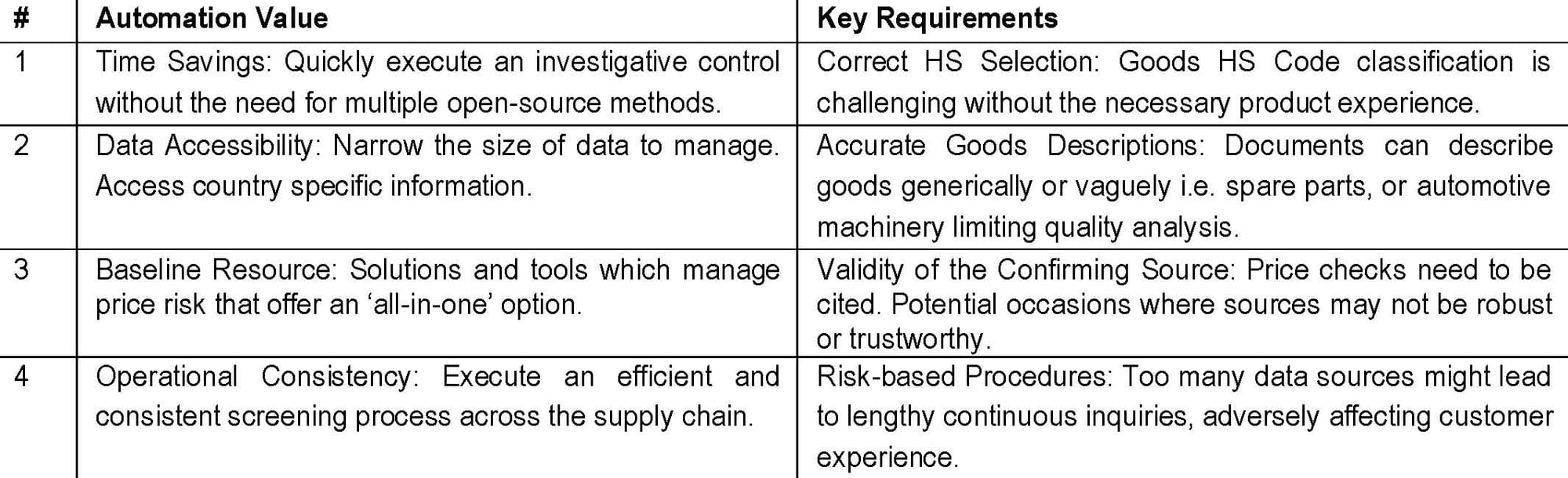

The technology presents potential benefits to increasing the efficiency of detecting price manipulation. However, it is still vulnerable to the shortcomings of the developing LLM environment and different shipping documents used throughout the supply chain. To determine effectiveness prior to implementation, an organization could consider the automation points below.

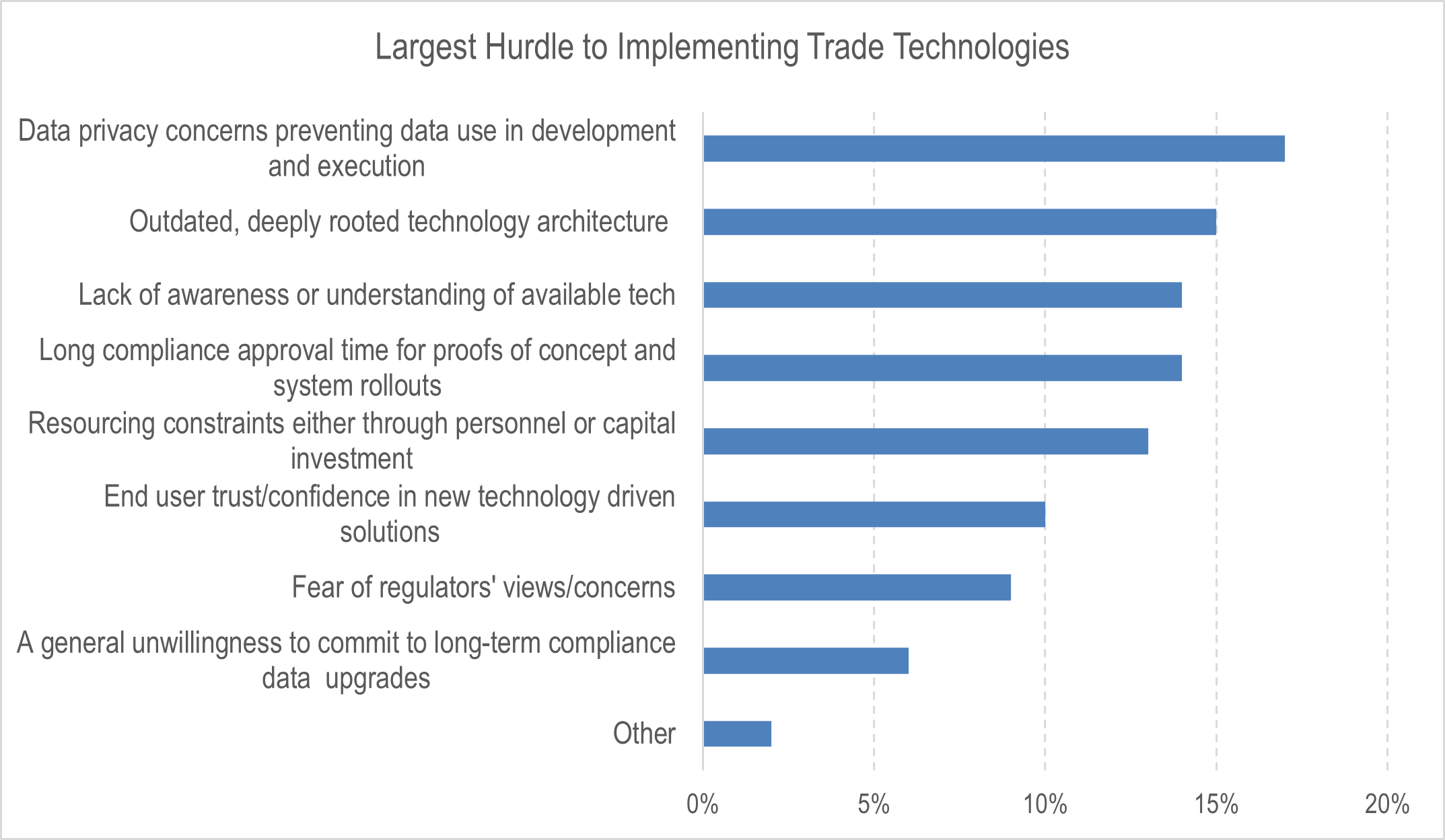

For an institution, while GenAI prompts can be used, they are unlikely to be usable across large transactional volumes or as a real-time transaction screening solution. Open-source GenAI tools are not fully integrated with screening processes, and inherently possess the vulnerabilities that might contribute to data leaks, data pollution, and breach of confidential information. The potential use of GenAI must surmount the hurdles of data privacy concerns and outdated technology architecture. In a recent survey, these points were reinforced by ITFA members as a key consideration.[[16]] Without an appropriate level of governance and data management, while displaying a reasonable level of accuracy, the use of GenAI will continue to have a slower adoption rate.

There are many ways to tackle the challenges of detecting price manipulation. There is no single standardized approach for every institution as consideration should be made to the inherent risk exposure. In this regard, the execution of a risk assessment could assist management in establishing an appropriate risk appetite and control structure. An isolated transaction-by-transaction approach, where price is evaluated using the details available on a trade document, only offers a narrow view of the overall customer and trade flows. Alternatively, consideration could be made to a wider contextual analysis into the trade transaction lifecycle and customer behavior, focusing on where trade risk originates. Once sufficiently quantified, organizations can step down into more granular aspects of pricing risk.

Taking any of the approaches above, requires organizations to ensure they are armed with the appropriate risk assessments, resources, training, customized testing, data controls, and technology. This creates an environment of rapid decision making that could more accurately dissect complex trade behaviors and transactions. The method of export and import differential pricing analysis, executed infrequently and on a reasonable basis, could assist organizations in targeting and concentrating on higher risk areas and goods.

The consistent promise of automation, such as LLMs and large reliable data sets, seeks to pull trade out of its historical paper processes. With proper oversight and governance, institutions with the appropriate levels of resources could experiment with different techniques to rapidly evolve their automation programs. In turn, create a more effective detection and investigations process.

Institutions should consider all the perspectives and weigh what is most effective in an environment where the receipt of data elements is inconsistent and the review and detection of price manipulation is likely not going to disappear.

Many thanks to those esteemed colleagues from the ITFA Financial Crime Compliance Initiative who provided expertise, guidance, and advice.

The views expressed by the authors in this publication do not represent their employers, any entity, government, or agency. Any content should not be interpreted in any capacity as regulatory guidance, recommendations, or interpretations of law. Such expressed views are to be considered individual opinions and perspectives.

[[1]]: Financial Action Task Force, Trade-based Money Laundering, Paris: France, 23 June 2006

[[2]]: The Joint Money Laundering Steering Group, “Current Guidance,” https://www.jmlsg.org.uk/guidance/current-guidance/

[[3]]: State Bank of Pakistan “Framework for Managing Risks of Trade Based Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing,” EPD Circular Letter No.08 (August 12, 2025) https://www.sbp.org.pk/epd/2025/FECL8-Annex.pdf

[[4]]: United States Government Accountability Office, “Countering Illicit Finance and Trade, Better Information Sharing and Collaboration Needed to Combat Trade Based Money Laundering,” Washington, DC, November 2021

[[5]]: United Arab Emirates, Financial Intelligence Unit, “Trade-Based Money Laundering, Updated Strategic Analysis Report,” Annual Report., International Tower, Fifth Floor, Al Karamah St., P.O Box 854, June 2024

[[6]]: Michael Corkery, Jessica Silver-Greenberg, “Banamex Fraud Exposes Challenges for Citi in Mexico,” The New York Times, March 11, 2014

[[7]]: Dawn, E-paper Editorial, “Solar Panels Scam,” 15 February 2025. Available at https://www.dawn.com/news/1892059

[[8]]: Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units, FATF, “Trade-Based Money Laundering, Trends and Developments,” Paris: France, December 2020

[[9]]: William Kuebler, Steven Lohr and James Sterrett, “Fighting for our Future: How—and Why—We Brought Wargames to an ROTC Program,” Modern War Institute at West Point (March 28, 2025), https://mwi.westpoint.edu/fighting-for-our-future-how-and-why-we-brought-wargames-to-an-rotc-program

[[10]]: World Bank, World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS), reviewed on November 7, 2025. Available at https://wits.worldbank.org/trade/country-byhs6product.aspx?lang=en

[[11]]: United States International Trade Commission, Data Web. https://dataweb.usitc.gov/

[[12]]: CME Group, Global Gas and Power Products, https://www.cmegroup.com/markets/energy/natural-gas/lng-japan-korea-marker-platts-swap.html

[[13]]: The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, “Advisory on the Use of Chinese Money Laundering Networks by Mexico-Based Transnational Criminal Organizations to Launder Illicit Proceeds,” Washington, DC, August 28, 2025

[[14]]: Byron McKinney and Edward R. Stoltenberg, “The Conquest of Military Dual-Use Goods Detection in Trade Finance,” International Trade Forfaiting Association, Financial Crime Compliance Initiative, June 18, 2025

[[15]]: The authors used the prompt “price of shirts originating in Bangladesh, shipped to USA”

[[16]]: International Trade Forfaiting Association, Financial Crime Compliance Initiative Survey, May 2025

Gain full access to analysis, cases, eBooks and more with a DCW Free Trial